Most AI pilots fail. Not “fail to exceed expectations” but fail completely. Zero measurable return. Project scrapped. Budget wasted.

MIT research from 2025 found that 95% of enterprise AI pilots don’t deliver measurable financial returns within six months. That’s not a typo. Ninety-five percent.

The good news: failure isn’t random. Pilots fail for predictable reasons. Design yours to avoid those reasons, and you dramatically improve your odds.

This guide covers how to structure an AI pilot that produces real results. Not a demo that impresses executives, but an experiment that proves whether AI works for your specific situation.

Why Most Pilots Fail

Before designing a successful pilot, understand why most don’t make it.

Wrong problem selection. Companies pick problems that sound AI-appropriate but aren’t actually good fits. Or they pick problems too complex to tackle in a pilot timeframe.

Unclear success criteria. Without defined metrics, there’s no way to know if the pilot worked. “It seemed helpful” isn’t a basis for investment decisions.

Volunteer bias. Pilots often attract early adopters who’d succeed with any tool. Results don’t generalize to typical users.

Insufficient resources. Pilots get started but not supported. No training, no troubleshooting, no iteration.

Wrong timeframe. Too short to see real results. Too long to maintain focus and urgency.

No comparison group. Without a control, you can’t distinguish AI impact from other factors.

Technology-first thinking. Starting with “let’s try this AI tool” instead of “let’s solve this problem.”

MIT’s research specifically attributes the 95% failure rate to “brittle workflows, weak contextual learning, and misalignment with day-to-day operations.” Translation: pilots that don’t fit how people actually work.

Pick the Right Problem

Your pilot lives or dies on problem selection.

Good pilot problems have these characteristics:

Measurable output. You can count something before and after. Time spent on tasks. Error rates. Output volume. Revenue influenced.

Contained scope. One team, one process, one use case. Pilots that touch multiple departments or workflows introduce too many variables.

Frequent occurrence. The task happens often enough that you’ll accumulate meaningful data during the pilot period.

Current pain. People already recognize the problem. You’re not convincing them something is broken, just offering a potential fix.

AI appropriateness. The task involves language, pattern recognition, content generation, or data analysis, areas where AI actually helps.

Low catastrophic risk. If AI makes mistakes, consequences are recoverable. Don’t pilot AI on tasks where errors cause major harm.

Willing participants. People in the pilot actually want to try it. Forcing adoption guarantees failure.

Examples of good pilot candidates:

- Sales team prospect research (measurable time, frequent task, contained to one team)

- First-draft content creation for marketing (countable output, clear before/after)

- Customer inquiry categorization (high volume, measurable accuracy)

- Meeting summary generation (frequent, easy to compare quality)

Examples of poor pilot candidates:

- “Use AI across the organization” (too broad)

- Critical legal document review (too risky for a pilot)

- Once-a-year strategic planning (too infrequent to measure)

- Process that nobody complains about (no baseline pain)

Define Success Criteria Before You Start

This step gets skipped constantly. It’s also the most important.

Before launching, write down exactly what success looks like. Be specific.

Primary metrics: The main things you’re measuring. Usually 2-3.

“Reduce average prospect research time from 45 minutes to under 20 minutes.”

“Increase content output from 4 pieces per week to 8 pieces per week with equivalent or better quality.”

“Achieve 85% accuracy on inquiry categorization compared to 72% current manual accuracy.”

Secondary metrics: Supporting data that provides context.

“User satisfaction score of 4+ out of 5.”

“No increase in downstream error rates.”

“At least 80% of pilot participants using the tool by week 4.”

Failure indicators: What would tell you to stop early.

“Quality scores drop below current baseline.”

“Less than 50% adoption after adequate training.”

“Significant security or compliance incidents.”

Write these down. Get stakeholder agreement. Revisit them only if circumstances fundamentally change, not because results are disappointing.

According to Menlo Ventures’ 2025 enterprise AI research, companies that define clear KPIs before deployment are significantly more likely to report positive ROI. The act of defining success criteria forces clarity about what you’re actually trying to achieve.

Size the Pilot Correctly

Too small, and results aren’t statistically meaningful. Too large, and you’ve committed significant resources to an unproven approach.

Pilot sizing guidelines:

Team size: 5-15 people is usually the sweet spot. Enough to generate meaningful data, small enough to support properly.

Duration: 8-12 weeks for most pilots. Less than 6 weeks rarely allows for adoption curve and behavior change. More than 16 weeks loses focus.

Scope: One primary use case. Maybe a secondary use case if closely related. Resist the urge to test everything at once.

MIT’s research found that mid-market organizations move from pilot to full implementation in about 90 days on average, while large enterprises take nine months or longer. Design your pilot to fit your organizational context.

Consider your comparison approach:

Option A: Before/after comparison. Measure the same people before and after AI adoption. Simple but doesn’t account for other changes during the period.

Option B: Control group. Some people use AI, some don’t, during the same period. Stronger evidence but requires careful group matching and can create fairness concerns.

Option C: A/B within tasks. Same person does some tasks with AI, some without. Works for high-volume, repeatable tasks.

Choose based on your situation and what level of evidence you need. If you’re asking for major investment based on pilot results, a control group strengthens your case.

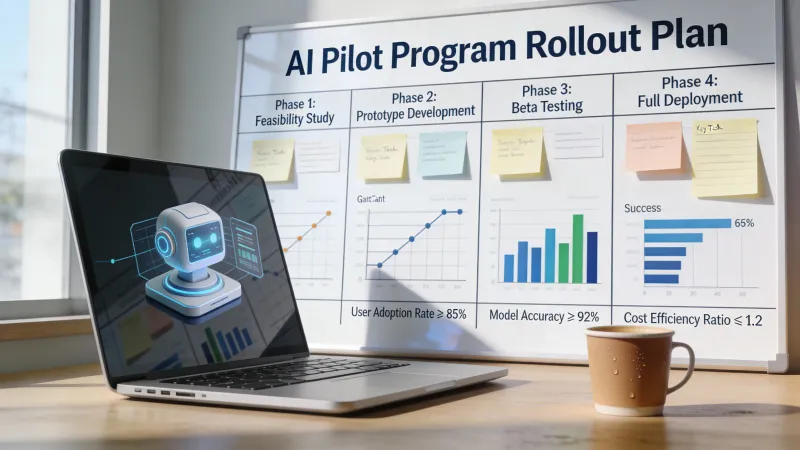

Structure the Pilot Timeline

A typical 12-week pilot timeline:

Weeks 1-2: Setup

- Finalize tool configuration

- Prepare training materials

- Brief participants on goals and process

- Collect baseline measurements

- Set up tracking mechanisms

Weeks 3-4: Training and Initial Adoption

- Conduct training sessions

- Provide hands-on practice

- Offer heavy support for questions

- Expect low productivity initially

- Document early issues

Weeks 5-8: Active Usage

- Daily/weekly use expected

- Regular check-ins with participants

- Ongoing support available

- Track metrics consistently

- Address problems as they emerge

Weeks 9-10: Stabilization

- Usage should be habitual

- Support needs decrease

- Focus on edge cases and refinements

- Continue metric tracking

Weeks 11-12: Evaluation

- Compile final metrics

- Conduct participant interviews

- Compare against success criteria

- Prepare findings report

- Determine recommendation

Adjust based on your specific situation, but maintain clear phases. The training-heavy early weeks are essential. Skipping them is a primary cause of pilot failure.

Select Participants Carefully

Who you include in the pilot matters more than most people realize.

Avoid all-volunteers. Self-selected groups skew toward enthusiasts. Results won’t generalize.

Avoid all-skeptics. Forcing resistant people guarantees failure.

Mix experience levels. Include tech-savvy and tech-cautious people. If AI only works for digital natives, that limits its value.

Include workflow variety. People who do the task slightly differently help identify edge cases.

Ensure time commitment. Participants need protected time for learning. Adding AI on top of already-maxed workloads fails.

Get manager buy-in. Participants’ managers must support the pilot, including accepting short-term productivity dips.

Selection conversation: “We’re testing whether AI can help with [task]. We want a mix of perspectives. This will require about [X hours] for training and [Y% of your task time] using the new tool. Your feedback will shape whether we roll this out more broadly. Interested?”

BCG’s 2025 research on AI at work found that while more than three-quarters of leaders and managers use generative AI regularly, frontline employee usage has stalled at 51%. Your pilot should include people from both groups.

Provide Adequate Support

Pilots fail when people get stuck and have no help.

Support mechanisms to build in:

Initial training. Not “here’s the tool, figure it out” but structured learning. Cover the basics, common use cases, and tips from early testing.

Documentation. Quick reference guides. Common prompts that work. Troubleshooting steps.

Dedicated support contact. Someone participants can reach with questions. Response within hours, not days.

Regular check-ins. Scheduled touchpoints to discuss what’s working and what isn’t.

Peer learning. Ways for participants to share discoveries with each other.

Problem escalation path. When issues exceed support contact’s knowledge, a clear path to technical help.

The first two weeks are critical. Expect heavy support needs. Budget time accordingly. Front-loading support prevents early frustration that kills pilots.

One useful practice: daily five-minute stand-ups during the first two weeks. “What worked yesterday? What didn’t? What do you need?” This surfaces problems before they fester.

Track and Document Everything

Your pilot produces two outputs: results and learning. Both require documentation.

Quantitative tracking:

- Baseline metrics (before pilot)

- Weekly metric updates during pilot

- Final metrics (end of pilot)

- Comparison calculations

Use whatever tracking approach fits your context. Spreadsheets work fine. The key is consistency.

Qualitative tracking:

- Weekly participant feedback

- Specific success stories (with details)

- Specific failures (with details)

- Workflow observations

- Unexpected discoveries

- Feature requests or limitations encountered

Create a shared document or channel where participants can log observations as they happen. Memory fades. Capture insights in real-time.

Technical tracking:

- Actual usage data (if available from the tool)

- Error rates

- Types of tasks attempted

- Types of tasks that work well vs. poorly

This documentation becomes invaluable for scaling decisions. “The pilot worked” is good. “Here’s exactly how people used it, what results they got, and what we learned” is much better.

Run a Honest Evaluation

Pilot end approaches. Time to assess.

Avoid two common mistakes:

Declaring success prematurely. Some positive results don’t mean the pilot worked. Compare against your pre-defined criteria, not against zero.

Explaining away failure. “It would have worked if…” is not success. Note the learning, but call failure what it is.

Evaluation framework:

Did we hit success criteria? Compare actual results to targets defined at the start. Be honest. “We achieved 70% of target” is useful information.

What worked well? Specific tasks, use cases, or situations where AI delivered clear value.

What didn’t work? Tasks where AI wasn’t helpful or made things worse. Be specific about why.

What surprised us? Unexpected positives or negatives. These often contain the most valuable learning.

What would we do differently? For both the pilot process and potential broader rollout.

Is there a path to scale? Based on results, does expanding make sense? What would need to change?

What’s the recommendation? Clear next step: proceed to scale, run another pilot with modifications, or discontinue.

According to McKinsey’s 2025 survey, less than 10% of organizations have scaled AI agents in any individual function, showing a substantial gap between initial pilots and broader deployment. Your evaluation should explicitly address what scaling would require.

Communicate Results Effectively

Your pilot findings need to reach decision-makers in a useful format.

Executive summary (one page):

- What we tested

- Key results vs. success criteria

- Main learning

- Recommendation

Detailed findings (2-3 pages):

- Methodology

- Quantitative results with comparisons

- Qualitative findings

- Challenges encountered and how addressed

- Participant feedback summary

Appendix:

- Raw data

- Full participant comments

- Technical notes

- Supporting documentation

Frame results honestly. If the pilot partially succeeded, say that. “We achieved 80% of target metrics, identified three use cases that work well and two that don’t, and have a clear path to improvement” is more credible than spin.

Include participant quotes. Real feedback from real users carries weight. “It cut my research time in half” from a salesperson means more than your summary statistics.

Connect results to business outcomes. Time saved converts to cost reduction. Quality improvements convert to customer impact. Make the business case explicit.

From Pilot to Scale

A successful pilot doesn’t automatically mean successful scaling. The transition requires planning.

Questions to answer before scaling:

Who’s next? Which teams or functions should adopt after the pilot group? Priority based on likely impact and readiness.

What changes? Pilot conditions rarely match broad deployment. What processes need modification? What support structures need expansion?

What training is required? Your pilot group had intensive support. How do you train at scale?

What infrastructure is needed? IT requirements, security reviews, procurement processes, license expansion.

Who owns this ongoing? Someone needs accountability for continued success.

What’s the budget? Scaling costs more than piloting. Build the business case from pilot data. Our building an AI business case guide covers this in detail.

What’s the timeline? Phased rollout usually works better than big-bang deployment.

MIT’s research found that enterprises run the most pilots but convert the fewest. Mid-market organizations move faster from pilot to full implementation. Large organizations need to explicitly address the transition gap.

For detailed guidance on expanding beyond pilots, see our scaling AI across the organization guide.

What if the Pilot Fails?

Not every pilot should succeed. That’s the point of piloting: learning cheaply what works and what doesn’t.

If your pilot fails to meet success criteria:

Document the learning. Why didn’t it work? Tool limitations? Wrong use case? Implementation problems? Organizational resistance? This knowledge has value.

Distinguish types of failure:

- Wrong problem (pilot this solution on a different problem)

- Wrong solution (pilot a different tool on this problem)

- Wrong timing (try again when conditions change)

- Fundamentally won’t work (stop investing)

Communicate honestly. “The pilot didn’t deliver expected results. Here’s what we learned and what we recommend next.” Hiding failure prevents organizational learning.

Decide on next steps. Another pilot with modifications? Different approach entirely? Pause and revisit later? Make a clear decision.

Failed pilots aren’t wasted if you extract learning. They’re wasted when you pretend they succeeded or bury the results.

Common Pilot Mistakes to Avoid

The demo pilot: Focused on impressing executives rather than testing real usage. Looks good in presentations, teaches nothing.

The too-short pilot: Two weeks isn’t enough to see behavior change. You’re measuring novelty effects, not sustainable value.

The uncontrolled pilot: No baseline, no comparison group, no way to attribute results to AI vs. other factors.

The unsupported pilot: Throw tool at people, hope they figure it out. Guarantees failure.

The hidden pilot: Done quietly without organizational visibility. Even if it works, no path to support or scaling.

The scope-creep pilot: Started with one use case, expanded to five mid-pilot. Now you can’t interpret any of the results.

The predetermined pilot: Decision already made, pilot is theater to justify it. Wastes everyone’s time.

Starting Your Pilot

Ready to begin? Here’s your checklist:

- Select your problem - One specific, measurable, AI-appropriate challenge

- Define success criteria - Specific metrics with targets, written down and agreed

- Choose participants - Mixed group with time and manager support

- Size appropriately - 5-15 people, 8-12 weeks, one use case

- Plan the timeline - Clear phases with support front-loaded

- Build support mechanisms - Training, documentation, help contact, check-ins

- Set up tracking - Baseline measurements, weekly updates, documentation system

- Brief stakeholders - Everyone knows what you’re testing and why

- Run it - With attention and support

- Evaluate honestly - Against pre-defined criteria

- Communicate results - Clear findings and recommendations

- Decide next steps - Scale, modify, or stop

AI pilots fail for predictable reasons. Design yours to avoid those reasons. Define success clearly, support participants adequately, track results consistently, and evaluate honestly.

The 5% of pilots that succeed aren’t lucky. They’re well-designed.