In January 2020, a team at OpenAI published a paper with a dry title: “Scaling Laws for Neural Language Models.” The paper itself was dense with equations and graphs that most people would never read.

But the implications were staggering.

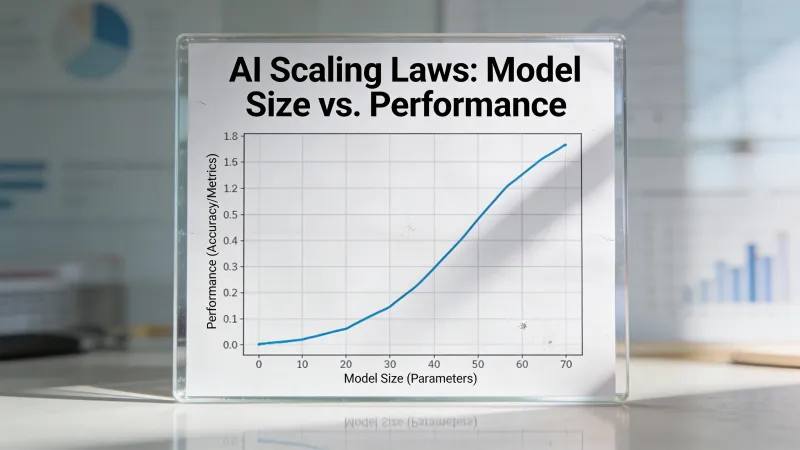

The researchers, led by Jared Kaplan, had discovered something that seemed almost too neat to be true: AI performance follows mathematical patterns that hold across seven orders of magnitude. Not rough correlations. Not approximate trends. Power laws with predictable curves.

This discovery changed how AI labs operate, where billions of dollars flow, and what futures seem possible.

The Core Finding

Performance improves predictably. That sentence contains an extraordinary claim that the 2020 OpenAI paper managed to substantiate through extensive experimentation.

The researchers trained dozens of language models of different sizes, on different amounts of data, using different amounts of compute. Then they plotted the results. What emerged was a family of smooth curves that followed precise mathematical relationships.

According to the original Kaplan et al. paper, “the loss scales as a power-law with model size, dataset size, and the amount of compute used for training.” This relationship held across models ranging from millions to billions of parameters.

Double your compute budget? Your model’s prediction error drops by a consistent, predictable amount. Double it again? Same proportional improvement. The curves were smooth all the way up.

This was not how anyone expected machine learning to work. Most assumed there would be diminishing returns, plateaus, unexpected cliffs where things stopped working. Instead, the graphs showed relentless, predictable improvement.

Why This Changed Everything

Before scaling laws, training a frontier AI model was like launching a rocket without knowing whether you had enough fuel to reach orbit, and you would not find out until the end of a months-long training run that cost tens of millions of dollars.

After scaling laws, labs could predict outcomes.

Want to know approximately how capable your next model will be? Look at your compute budget and consult the curves. Planning your data collection? The laws tell you how much you need. Deciding whether to build a bigger cluster? You can estimate the capability gains.

AI became, in some sense, an engineering problem rather than a scientific mystery. Not fully, not completely, but enough to make billion-dollar bets feel tractable.

The implications rippled outward. Companies could now raise money based on projected model capabilities. Hardware manufacturers could estimate demand. Researchers could plan multi-year roadmaps. The scaling laws gave the entire industry a planning framework it had never had.

The Chinchilla Correction

The first scaling laws were not quite right.

The Kaplan paper suggested that model size mattered more than dataset size. If you had limited compute, spend it on a bigger model. GPT-3, with its 175 billion parameters trained on “only” 300 billion tokens, reflected this philosophy.

In March 2022, DeepMind published what became known as the Chinchilla paper. They trained over 400 language models and found something different.

The optimal approach was to scale model size and training data together, roughly in proportion. Their conclusion: existing models were undertrained. A smaller model trained on more data could outperform a larger model trained on less.

Chinchilla itself proved the point. At 70 billion parameters (less than half of GPT-3) trained on 1.4 trillion tokens (nearly five times GPT-3’s data), it matched or beat the much larger model.

The new rule was approximately 20 tokens per parameter for compute-optimal training. This ratio became a benchmark that every AI lab knew by heart.

The Practical Reality of Scale

Numbers like “175 billion parameters” and “1.4 trillion tokens” are hard to grasp. Let me make them concrete.

Training GPT-3 required roughly 3.14 x 10^23 floating-point operations. That is 314,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 individual calculations. The training run reportedly cost between $4 million and $12 million in compute alone.

GPT-4’s training cost has been estimated at over $100 million. The compute requirements grow faster than improvements in hardware efficiency.

This creates a particular dynamic in the industry. On Hacker News, commenter bicepjai observed: “as progress depends more on massive training runs, it becomes capital-intensive, less reproducible and more secretive; so you get a compute divide and less publication.”

The capital requirements filter who can participate. A university lab cannot compete on raw scale with a company that can spend $100 million on a single training run. The scaling laws created a world where progress requires resources that few possess.

What the Laws Say (and What They Do Not)

The scaling laws tell you that loss decreases predictably. Loss, in this context, means how wrong the model is when predicting the next word. Lower loss means better predictions.

But here is what the laws do not tell you: what the model can actually do.

The relationship between loss and capabilities is complex. A model might get incrementally better at predicting text while suddenly gaining the ability to solve math problems it could not solve before. These “emergent capabilities” appeared at specific scale thresholds that the laws did not predict.

Few-shot learning, where a model learns new tasks from a handful of examples, emerged around the 100 billion parameter mark. Chain-of-thought reasoning appeared at similar scales. These capabilities were not just quantitative improvements on existing abilities. They were qualitatively new.

The scaling laws describe a smooth curve. Reality showed sudden jumps.

The Open Research Problem

Not everyone celebrated the scaling paradigm.

On Hacker News, researcher gdiamos commented: “I especially agree with your point that scaling laws really killed open research. That’s a shame and I personally think we could benefit from more research.”

The concern is structural. If progress requires massive compute, only well-funded labs can make progress. If only well-funded labs make progress, most researchers cannot contribute to the frontier. Academic computer science departments, historically the source of breakthrough ideas, get sidelined.

gdiamos continued: “If scaling is predictable, then you don’t need to do most experiments at very large scale. However, that doesn’t seem to stop researchers from starting there.”

There is something ironic here. The scaling laws theoretically let you predict large-scale results from small-scale experiments. In practice, the incentives push everyone toward scale anyway. You cannot publish about GPT-5-scale capabilities if you do not have GPT-5-scale resources.

Beyond Pre-Training: New Frontiers

The original scaling laws focused on pre-training, the initial phase where a model learns to predict text. But the AI development pipeline has more stages.

Recent research has identified at least three distinct scaling regimes:

Pre-training scaling follows the original Kaplan and Chinchilla laws. Bigger models trained on more data predict text better.

Post-training scaling covers fine-tuning and alignment. The relationship between compute spent on human feedback and model behavior follows its own patterns, distinct from pre-training.

Inference scaling is the newest discovery. OpenAI’s o1 model demonstrated that letting a model “think longer” at inference time improves reasoning performance. This suggests another dimension where more compute yields better results.

The existence of multiple scaling laws implies continued improvement paths even if pre-training scaling slows down. A model can potentially get better through more sophisticated post-training or by taking more time to reason through problems.

The Data Wall

The Chinchilla correction created a new problem.

If optimal training requires scaling data alongside model size, and current frontier models have already consumed most high-quality text on the internet, where does the next training dataset come from?

Estimates suggest the indexed web contains roughly 510 trillion tokens. That sounds like a lot until you consider that most of it is low-quality, repetitive, or outright garbage. The highest-quality text, the kind that actually teaches a model to reason well, is a small fraction.

Current approaches to the data wall include:

Synthetic data: Having AI generate training data for the next generation of AI. This works to some extent but carries risks of model collapse if done carelessly.

Multimodal expansion: Training on images, video, and audio alongside text opens new data sources. The world contains far more visual information than written text.

Higher-quality curation: Perhaps the issue is not quantity but quality. Better filtering might extract more learning signal from existing data.

New data creation: Some labs are reportedly paying for or creating proprietary content specifically for training.

None of these clearly solves the problem. The data wall remains one of the central constraints on continued scaling.

The Diminishing Returns Debate

In late 2024 and into 2025, reports emerged that frontier model improvements were slowing. The latest models were not leaping ahead as dramatically as previous generations had.

Some interpreted this as the death of scaling. The party was over. The laws had run their course.

Others pointed out that the original scaling laws predicted diminishing returns from the start. The curves are logarithmic, not exponential. Each doubling of compute buys a smaller absolute improvement than the last. This was always the expected pattern.

The debate hinges on a question nobody can definitively answer: are we seeing the expected slowdown from logarithmic improvement, or a fundamental ceiling on what scaling can achieve?

Different observers read the same data differently. Progress continues, but at what rate? And is that rate sufficient for the capabilities people want?

Predictions That Did and Did Not Hold

The scaling laws made specific predictions. Some held up. Some did not.

Held up: The basic relationship between compute and loss has remained remarkably consistent across different architectures and approaches. The fundamental curves work.

Partially held: The Chinchilla optimal ratio turned out to be optimal for training efficiency but not for deployment efficiency. Modern models like Llama 3 train on 200 tokens per parameter, far beyond Chinchilla optimal, because inference costs matter more than training costs for products used at scale.

Did not hold: The original Kaplan paper’s prediction that model size matters more than data size was simply wrong. Chinchilla demonstrated this decisively.

Unclear: Whether scaling continues to produce useful capabilities beyond current scales remains unresolved. The laws predict continued loss reduction but not whether that loss reduction translates to capabilities humans care about.

What Scaling Cannot Tell You

The scaling laws are silent on several critical questions.

They do not tell you whether a model will hallucinate. Loss reduction does not guarantee factual accuracy.

They do not tell you whether a model will be safe or aligned with human values. A model can predict text very well while being helpful, harmless, or dangerous.

They do not tell you whether a model will be good at any specific task. General loss reduction does not guarantee performance on the particular problem you care about.

They do not tell you when qualitatively new capabilities will emerge. The laws describe smooth curves, but capabilities appear discontinuously.

These gaps matter. They mean that even with perfect knowledge of scaling laws, you cannot fully predict what a model will be like. The laws constrain the possibility space without determining it.

The Philosophical Puzzle

There is something philosophically strange about scaling laws.

Why should language prediction follow such clean mathematical patterns? The training data is a messy, inconsistent snapshot of human writing. The architecture is a series of engineering choices. The optimization process is stochastic. Yet the outcome follows power laws across seven orders of magnitude.

Some see this as evidence that intelligence has mathematical structure waiting to be discovered. Others see it as a suspicious coincidence that might not hold forever. Still others argue it simply reflects the statistical properties of language itself.

The scaling laws work. Why they work remains genuinely unclear.

Where This Leaves Us

The scaling laws gave the AI industry something it desperately needed: a planning framework. They enabled billion-dollar investments, multi-year roadmaps, and confident predictions about future capabilities.

But frameworks can become prisons.

The focus on scaling may have crowded out other approaches. Massive compute became the default solution even when smaller experiments could have answered the same questions. Academic research got marginalized. Alternative architectures got less attention.

Now, as pre-training scaling shows signs of strain, the industry is discovering other paths. Inference scaling. Synthetic data. Better training algorithms. Post-training optimization. These approaches existed all along but lived in scaling’s shadow.

The scaling laws were a discovery about how AI works. They were also a choice about how to pursue progress. Whether that choice was optimal, whether we would be further ahead today with more diverse approaches, is a question nobody can answer with certainty.

What we do know: the curves still slope downward. Compute still helps. The laws still hold, even if the gains get harder to capture.

The next breakthrough might come from more scale, or from something else entirely.