Somewhere between your question and the AI’s answer, a decision happens. Not one decision. Thousands.

Every single word the model writes involves a choice among alternatives that could have fit in that spot. “Blue” or “clear” or “dark.” “Therefore” or “so” or “consequently.” Each choice shapes everything that follows. Temperature is the setting that controls how those choices get made.

Most people never touch it. They should.

The Probability Machine

When a language model generates text, it does not retrieve answers from a database and it is not searching the internet for the best response to your question or looking up the correct answer in some vast encyclopedia. It predicts. Given everything it has read during training and everything you have written in your prompt, the model calculates the probability that each possible next word would naturally follow.

For “The weather today is ___,” the model might compute:

- sunny: 28% probability

- nice: 15% probability

- terrible: 8% probability

- apocalyptic: 0.003% probability

These probabilities come from patterns absorbed during training, millions of examples of how humans complete similar sentences, weighted and combined through layers of neural network math that even the engineers who built it cannot fully explain.

Temperature changes what happens next.

What Temperature Actually Does

The term comes from physics. In statistical mechanics, temperature describes how energy distributes across a system. Cold systems concentrate energy in predictable patterns. Hot systems spread energy chaotically.

The math carries over almost directly to language models, and here the word “temperature” is not a metaphor but an actual technical term borrowed from thermodynamics because the equations look nearly identical.

Low temperature sharpens the probability distribution. If “sunny” had 28% probability and “nice” had 15%, lowering temperature might push those to 45% and 8%. The gaps widen. The favorite becomes more dominant. The model becomes increasingly likely to pick the highest-probability option, and lower-probability alternatives almost never get chosen.

High temperature flattens the distribution. Those same probabilities might become 22% and 18%. The gaps shrink. Second-place and third-place options get more chances. The model samples more broadly from its probability distribution, including words it would almost never choose at low temperature.

At temperature zero, the model always picks the single most probable next word. Every single time. Run the same prompt a hundred times, get the same output a hundred times. This is sometimes called greedy decoding.

At temperature one, the model samples directly from its raw probability distribution without modification. A word with 10% probability has a 10% chance of being selected.

Above temperature one, lower-probability options get boosted. The distribution flattens further. Words that had tiny chances now have real ones.

The Creativity Illusion

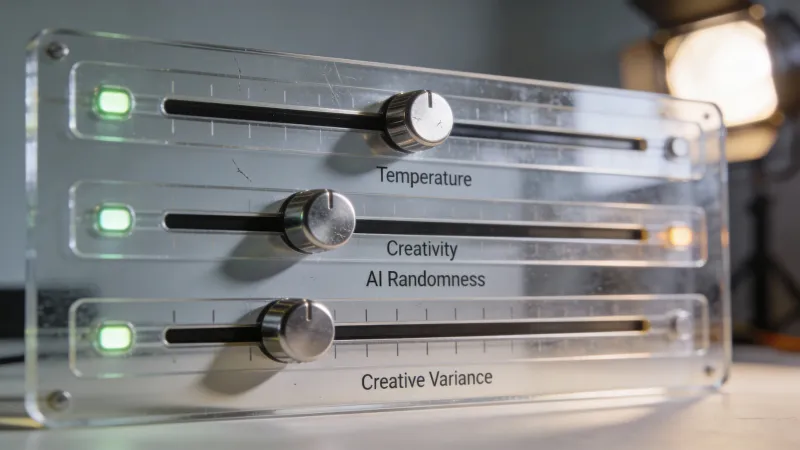

Many AI interfaces label their temperature slider “creativity.” This is marketing. Not engineering.

Randomness is not creativity. Choosing unexpected words is not the same as having interesting ideas, and the distinction matters enormously for how you should think about this setting.

A Hacker News user named spywaregorilla put it well: temperature is “more like ‘willingness to choose less likely answers.’” That framing helps. Less likely is not the same as better or more creative. Sometimes the less likely word is surprising and delightful. Sometimes it is just wrong.

Higher temperature does produce more varied output. The model explores more of its probability space, and that exploration occasionally surfaces combinations you would never have seen at low temperature. But “occasionally” is the key word. Most of the time, low-probability words were low-probability for good reasons.

Another commenter, noodletheworld, made the point bluntly: “Randomising LLM outputs (temperature) results in outputs that will always have some degree of hallucination. That’s just math. You can’t mix a random factor in and magically expect it to not exist.”

That is the tradeoff. Determinism produces consistency and boredom. Randomness produces variety and errors. Temperature is the dial between those poles.

The Zero Problem

If determinism avoids hallucination, why not always use temperature zero?

Because determinism has its own pathology. Models at zero temperature get stuck. They fall into loops. They repeat themselves obsessively. They default to the most generic, most probable phrasing for everything, producing text that reads like it was written by a cautious bureaucrat who never wants to say anything interesting.

Avianlyric on Hacker News explained the dynamic: “Setting the temperature of an LLM to 0 effectively disables that randomness, but the result is a very boring output that’s likely to end up caught in a never ending loop.”

Some amount of randomness is necessary for interesting output. The question is how much.

Top-P: A Different Approach

Temperature scales probabilities. Top-p (also called nucleus sampling) restricts which options get considered at all.

The model still calculates probabilities for every possible next word. But instead of scaling those probabilities, top-p draws a cutoff. If you set top-p to 0.9, the model sorts all words by probability, adds them up starting from the most likely, and stops when it reaches 90% cumulative probability. Everything below that line is eliminated. The model then samples only from the remaining options.

This approach has an advantage that temperature lacks. It adapts.

When the model is confident and one word dominates the probability distribution, top-p naturally selects from a small set. When the model is uncertain and probabilities spread across many options, top-p includes more candidates. Temperature applies the same scaling regardless of context. Top-p responds to the model’s own confidence level.

In practice, top-p tends to produce more consistent output quality across different types of prompts. Temperature can work beautifully for one prompt and terribly for another. Top-p smooths out those extremes.

Top-K: The Blunt Instrument

Top-k is simpler and cruder. It considers exactly k options, no matter what.

Set top-k to 50, and the model only samples from the 50 most probable next words. Set it to 5, and you get only 5 options. The actual probability values do not matter for the cutoff, only the ranking.

This creates obvious problems. Some contexts have clear right answers where fewer than 50 options make sense. Others have wide-open possibilities where 50 is far too restrictive. Top-k cannot tell the difference.

Most production systems prefer top-p to top-k. The adaptability matters.

How Settings Interact

Here is where people get confused. These parameters can work together, but they often fight each other.

The typical processing order is: calculate probabilities, apply temperature scaling, apply top-p or top-k filtering, then sample from what remains.

Temperature happens first. It reshapes the entire distribution. Then top-p or top-k cuts off the tail. The result depends on both settings, and the interaction can be unpredictable.

Most documentation recommends adjusting one or the other, not both. If you are using top-p, leave temperature at 1.0 so you are working with the raw distribution. If you are adjusting temperature, set top-p to 1.0 (which disables it) so temperature has full control.

Adjusting both at once is not wrong, but it makes outcomes harder to predict and troubleshooting harder when output goes sideways.

Min-P: The Newcomer

Recent months have seen growing enthusiasm for a newer approach called min-p sampling, particularly among people running open-source models locally.

Min-p sets a minimum probability relative to the top option. If the most likely word has 50% probability and min-p is set to 0.1, any word with less than 5% probability (one-tenth of 50%) gets eliminated.

Like top-p, this adapts to context. When the model is confident, min-p is permissive because even moderately likely options clear the threshold. When the model is uncertain, min-p is restrictive because nothing clears a high bar.

API providers like OpenAI and Anthropic do not currently offer min-p. You will only encounter it using local models through tools like llama.cpp or text-generation-webui. But if you are experimenting with open weights models, min-p is worth understanding.

Practical Guidance

Different tasks call for different settings. Here is what actually works.

For code generation: Low temperature. Between 0.0 and 0.3. Syntax errors are not creative. Logic bugs are not interesting surprises. Code either works or it does not, and higher randomness just produces more broken output.

For factual questions: Low temperature. The correct answer to “What is the capital of France?” is Paris. There is no creative alternative that improves on that. Randomness can only make the answer worse.

For business writing: Moderate temperature. Between 0.3 and 0.6. You want professional and polished, not robotic and repetitive. Some variation keeps the prose alive. Too much variation introduces errors or strange word choices that undermine credibility.

For creative writing: Higher temperature. Between 0.7 and 1.0. Here randomness actually helps. Unexpected word choices create surprise. Unusual combinations produce fresh images. You want the model exploring its possibility space, not defaulting to cliches.

For brainstorming: Highest temperature. Between 0.9 and 1.2. You explicitly want unexpected output. You are looking for ideas you would not have thought of, and the whole point is to surface low-probability options. Generate many outputs and curate afterward.

The Model Matters

Different models respond differently to temperature changes.

Larger models tolerate higher temperatures better. They have absorbed more patterns, more ways of completing any given thought. When they sample from low-probability options, those options are still informed by vast training. Smaller models have thinner knowledge. Their low-probability outputs are more likely to be nonsense.

Newer models also tend to handle temperature more gracefully. Improvements in training and architecture have reduced the gap between high-temperature and low-temperature output quality. What would have produced gibberish in GPT-2 might produce interesting alternative phrasings in GPT-4.

If you are using a cheaper or smaller model tier, keep temperature lower. With powerful models, you have more room to experiment.

Beyond the Basics

Most users encounter only temperature, and maybe top-p. API users might also see:

Frequency penalty discourages repeating words already used in the output. Higher values mean stronger discouragement. This helps with the repetition problem at low temperatures without adding pure randomness.

Presence penalty encourages introducing new topics rather than dwelling on what has already been mentioned. Similar to frequency penalty but more about conceptual novelty than word repetition.

Max tokens controls output length. Not about randomness at all, just about when the model stops generating.

These settings matter most for developers building applications on top of language model APIs. For typical chat use, temperature and top-p are the ones worth understanding.

Settings Are Not Strategy

Here is what I wish someone had told me when I started experimenting with these controls: tuning parameters is not the same as giving good instructions.

A brilliant prompt at default settings will outperform a mediocre prompt at perfect settings. Clear context beats clever temperature choices. Specific examples beat tweaked top-p values. The fundamentals of communicating well with language models matter more than parameter optimization.

That said, parameters do matter at the margins. Once you have a good prompt, adjusting temperature can meaningfully improve results for your specific use case. The gains are real. They are just not the first gains you should pursue.

The Uncomfortable Truth

Temperature settings reveal something people sometimes prefer not to think about: language models are probabilistic systems making statistical choices, not reasoning engines arriving at correct answers.

When you turn temperature to zero and get deterministic output, you are not getting the right answer. You are getting the most probable answer. Those are not the same thing. When you turn temperature up and get varied output, you are not getting creative answers. You are getting sampled answers. Those are also not the same thing.

The model does not know which word is correct. It knows which word is probable. Temperature controls how strictly it follows that probability versus how much it explores alternatives. Neither choice makes the model smarter or more accurate. Both choices just change which outputs from its probability distribution you actually see.

Understanding that distinction changes how you use these tools. You stop expecting the right settings to unlock hidden capability. You start thinking about which sampling strategy fits your particular task. You become comfortable with the reality that language models are powerful and useful and also fundamentally different from how intelligence actually works.

The temperature slider is not a creativity dial. It is a randomness dial. Sometimes randomness serves you. Sometimes it does not. Knowing the difference is most of what there is to know.