You’ve used ChatGPT. Maybe daily. But how does it actually work?

The honest answer involves a lot of matrix math, some clever engineering tricks from 2017, and a training process that relies on humans rating outputs. The technology is remarkable. It’s also more mechanical than most people realize, which makes both its capabilities and its failures easier to understand once you see the machinery.

Let’s open it up.

The Foundation: Predicting the Next Word

At its core, ChatGPT does one thing. It predicts the next word in a sequence of text, then uses that prediction to generate the word after that, and the word after that, until it reaches a stopping point. That’s it. Every essay it writes, every code snippet it produces, every conversation it holds emerges from this single operation performed billions of times.

As user akelly explained on Hacker News when describing ChatGPT’s architecture: “Start with GPT-3, which predicts the next word in some text and is trained on all the text on the internet.” That’s the foundation. Everything else builds on top of next-word prediction.

The model doesn’t “think” in any human sense. It calculates probability distributions over its vocabulary of tokens (roughly 50,000 word fragments) and samples from those distributions. When you ask it a question, it’s not retrieving stored facts from a database. It’s generating text that statistically follows from your prompt based on patterns it learned during training.

This explains both its strengths and its strange failure modes. It can write fluently because it has seen trillions of words arranged in fluent sequences. It can hallucinate false information because statistically plausible text isn’t the same as true text.

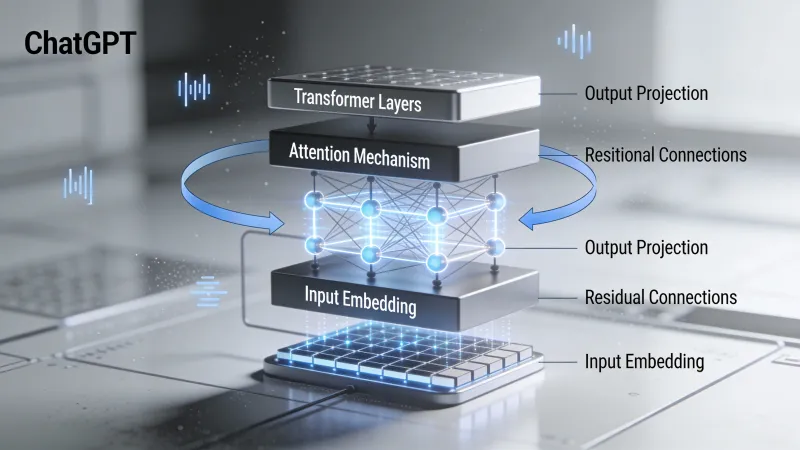

Transformers: The Architecture That Changed Everything

ChatGPT runs on a neural network architecture called a transformer. Google researchers introduced it in a 2017 paper titled “Attention Is All You Need.” The title references a Beatles song, but the paper transformed natural language processing more than any single publication in the field’s history.

Before transformers, language models processed text sequentially. Word by word. This created a bottleneck. Information from the beginning of a long passage would fade as the model processed later parts. Earlier approaches using recurrent neural networks could technically handle long sequences, but they struggled in practice.

Transformers fixed this through a mechanism called attention.

Attention: The Key Innovation

What is attention? At a simplified level, it lets each word in a sequence look at every other word and decide which ones matter most for understanding its meaning.

Consider the sentence: “The cat sat on the mat because it was tired.” What does “it” refer to? Humans know instantly that “it” refers to the cat, not the mat. But how would a computer figure that out?

With attention, the model computes scores between “it” and every other word in the sentence. The word “cat” gets a high attention score because, across the billions of examples the model saw during training, pronouns like “it” in similar positions usually referred back to animate nouns like “cat” rather than inanimate nouns like “mat.”

In a Hacker News discussion about GPT architecture, user yunwal described the query-key mechanism this way: “Q (Query) is like a search query. K (Key) is like a set of tags or attributes of each word.” Each word asks a question (the query) and every word has descriptive information (the key). The attention mechanism matches queries to relevant keys, allowing words far apart in a sentence to directly influence each other’s representations.

This happens across multiple “attention heads” simultaneously, with different heads learning to track different kinds of relationships: syntactic structure, semantic meaning, coreference, and patterns humans haven’t named.

The Transformer Stack

A full transformer isn’t just one attention layer. GPT models stack many transformer blocks on top of each other. GPT-3 has 96 layers. Each layer refines the representation of the input text, building increasingly abstract understanding as information flows through the network.

What emerges from all these layers and attention computations? Something that looks almost like comprehension, even though it’s built entirely from statistical patterns and linear algebra. The model develops internal representations that capture meaning surprisingly well, despite never having been explicitly told what words mean.

In the same Hacker News thread, chronolitus (who wrote a visual explainer on the GPT architecture) observed: “After the model is trained it all really boils down to a couple of matrix multiplications!” Technically true, though those multiplications happen across billions of parameters in careful arrangements that took years of research to discover.

Training: Where the Knowledge Comes From

How does ChatGPT learn to do what it does? Through two distinct phases, each essential to the final product.

Phase One: Pretraining

First, the model is trained on massive amounts of text. The exact training data for ChatGPT isn’t public, but GPT-3 was trained on hundreds of billions of words from books, websites, Wikipedia, and other text sources. The objective is simple: given a sequence of words, predict the next word.

This is called self-supervised learning because the training signal comes from the text itself. No human has to label anything. The model just reads enormous amounts of text and learns to predict what comes next.

Through this process, the model picks up remarkable capabilities. It learns grammar. It learns facts about the world (though imperfectly). It learns to code because it saw millions of code files. It learns to write poetry because it saw poetry. It learns how conversations flow because it saw conversations.

As user ravi-delia explained in a discussion about how ChatGPT works: “In learning to predict the next token, the model has to pick up lots of world knowledge. It has seen lots of python, and in order to predict better, it has developed internal models.”

But pretraining alone doesn’t produce ChatGPT. A pretrained model is an autocomplete engine. Ask it a question, and it might complete your text by asking more questions, or generating any other kind of text that statistically follows from your input. It won’t reliably answer questions the way a helpful assistant would.

Phase Two: Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF)

This is where OpenAI’s secret sauce comes in. After pretraining, ChatGPT was fine-tuned using human feedback.

The process works roughly like this. First, humans write example conversations demonstrating how an ideal AI assistant should respond. These examples teach the model the format and style of helpful responses.

Then comes the clever part. The model generates multiple responses to the same prompt. Human raters rank these responses from best to worst. Using these rankings, OpenAI trains a separate “reward model” that learns to predict how humans would rate any given response.

Finally, the language model is further trained to produce responses that score highly according to the reward model. This is the reinforcement learning step: the model learns to maximize a reward signal derived from human preferences.

The result is a model that doesn’t just complete text statistically. It generates responses that humans have taught it are helpful, harmless, and honest. In that same Hacker News thread, user hcks mentioned: “I personally worked as a ‘human trainer’ for the fine tuning of ChatGPT. The pay was 50$ per hour.”

Thousands of hours of human judgment went into making ChatGPT conversational rather than just generative.

What ChatGPT Can Do (and Why)

Given this architecture and training, certain capabilities make sense.

Fluent text generation: The model saw trillions of words. It knows what fluent English looks like. Generating grammatical, coherent text is exactly what it was optimized to do.

Following instructions: RLHF specifically trained it to follow prompts helpfully. When you ask for a list, it gives a list. When you ask for code, it writes code. Human raters rewarded responses that did what users asked.

Explaining concepts: It has seen millions of explanations of millions of topics. When you ask it to explain quantum physics, it draws on patterns from all those explanations to generate a new one tailored to your question.

Writing code: Same principle. It has seen enormous amounts of code with comments explaining what the code does. It can generate code that follows those patterns.

Translation between languages: The model saw text in many languages, often with parallel translations. It learned correspondences between languages from this data.

Adapting to context: The attention mechanism lets it track context across thousands of tokens. It remembers what you said earlier in the conversation because that information directly influences its predictions.

What ChatGPT Cannot Do (and Why)

The limitations are equally predictable once you understand the architecture.

Guaranteed factual accuracy: The model generates statistically likely text, not verified facts. If a plausible-sounding false statement fits the statistical patterns, the model will generate it. It has no separate fact-checking mechanism. No database of verified truths. Just patterns learned from text that included both accurate and inaccurate information.

Mathematical reasoning: Numbers are just tokens to the model. As bagels noted in a Hacker News discussion on GPT architecture: “Numbers are just more words to the model.” It can pattern-match simple arithmetic it has seen many times, but novel calculations often fail because the model is generating text that looks like correct math, not actually computing.

Consistent long-term memory: Within a conversation, context is limited by the model’s context window (the maximum number of tokens it can process at once). Across conversations, it remembers nothing unless explicitly told. Each conversation starts fresh.

Access to current information: The model’s knowledge comes from training data with a cutoff date. It cannot browse the internet, access databases, or know about events after its training unless given that information in the prompt.

True understanding: This is the philosophical one. The model manipulates symbols according to learned statistical patterns. Whether this constitutes “understanding” in any meaningful sense is debated.

In a thread about LLMs being overhyped, user wan23 put it bluntly: “There is a lot of knowledge encoded into the model, but there’s a difference between knowing what a sunset is because you read about it on the internet vs having seen one.” The model has never experienced anything. It has only seen descriptions of experiences.

In the same thread, user Jack000 compared LLMs to aliens lacking sensory experience, noting that they possess superhuman pattern recognition but work with incomplete information. They can process language better than any system before them, but they’re missing the grounding that comes from actually existing in the world.

The Scale That Makes It Work

Part of what makes ChatGPT effective is sheer scale. GPT-3 has 175 billion parameters. GPT-4 is larger (exact size undisclosed). Each parameter is a number that gets tuned during training. More parameters mean more capacity to store and represent patterns.

The training compute is staggering. Training GPT-4 reportedly cost over $100 million in computing resources. The model saw more text during training than any human could read in thousands of lifetimes.

This scale matters because transformers exhibit emergent capabilities at sufficient size. Abilities that don’t exist in smaller models suddenly appear in larger ones. The model doesn’t just get incrementally better at the same tasks. New capabilities emerge that weren’t explicitly trained.

Why this happens is an open research question. But it suggests that the architecture has room to discover patterns and capabilities beyond what its designers anticipated.

The Stopping Problem

One thing that often puzzles people: how does ChatGPT know when to stop generating text?

The model’s vocabulary includes special tokens. One of these represents “end of output.” As user amilios explained in the Hacker News thread on ChatGPT: “It predicts a special end-output token, something analogous to ‘EOF.’” When the model predicts this token as the most likely next token, it stops generating.

This is trained through examples. During fine-tuning, the model sees many examples of conversations where the assistant gives a complete response and then stops. It learns to predict the end-of-output token at appropriate points.

Temperature: Controlling Randomness

When ChatGPT generates text, it doesn’t always pick the single most probable next token. A parameter called “temperature” controls how much randomness enters the selection.

At temperature 0, the model always picks the highest-probability token. The output is deterministic and repetitive. At higher temperatures, less likely tokens have a better chance of being selected. The output becomes more creative but also more unpredictable.

As user doctoboggan explained in a Hacker News thread about GPT: “At temperature of 0 the highest probability token is chosen.”

This is why you can ask ChatGPT the same question twice and get different answers. The randomness is intentional. It makes conversations feel more natural and responses more varied.

Why This All Matters

Understanding how ChatGPT works changes how you use it.

If you know it’s a pattern-matching statistical engine, you won’t expect it to have reliable facts about obscure topics. You’ll verify important claims. You’ll understand that “confidently stated” doesn’t mean “true.”

If you know it’s trained on human feedback to be helpful, you’ll understand why it tries to please you even when it should push back. The reward model favored responses that humans rated highly, and humans often rated agreeable responses highly.

If you know attention lets it track context, you’ll use that context effectively. Put important information early in long prompts. Remind it of key constraints. Reference earlier parts of the conversation.

The technology is genuinely impressive. It represents a fundamental advance in what computers can do with language. But it’s not magic. It’s matrix multiplication at scale, trained on human text and human feedback, producing outputs that resemble human communication because that’s what it was optimized to produce.

The Watershed Moment

ChatGPT wasn’t the first large language model. GPT-3 came out in 2020. But as user herculity275 observed in a Hacker News thread on why LLMs suddenly became popular: “ChatGPT was the watershed moment for the tech because suddenly anyone in the world could sign up for free.”

That accessibility mattered. User jerpint added: “Not to mention without needing expertise to deploy the thing.”

The underlying technology had been advancing for years. Transformers came out in 2017. GPT-2 in 2019. GPT-3 in 2020. But those required technical knowledge to access. ChatGPT put the same technology in a chat window that anyone could use.

User xg15 captured why this felt different from earlier chatbots: “Understanding text in the depth that ChatGPT (and GPT-3) appear to understand the prompts is something entirely different.” Previous systems could generate fluent text. This one seemed to comprehend.

A Machine That Learned to Seem Like It Thinks

The question I keep coming back to: what does it mean that a system with no understanding, no experience, no goals beyond token prediction can produce text this coherent?

The model was trained to predict probable words. Through that simple objective, applied at enormous scale, it developed something that looks remarkably like comprehension. It can explain concepts. Solve problems. Write in different styles. Hold conversations that feel natural.

But there’s no one home. No experience behind the responses. No understanding in any sense we’d recognize. Just statistical patterns learned from text written by billions of humans who do understand, who have experienced, who know what sunsets actually look like.

Either we’ve underestimated what statistical learning can achieve. Or we’ve overestimated what producing coherent language requires.

Maybe the answer isn’t one or the other.