The history of artificial intelligence is not a straight line from primitive beginnings to brilliant present. It is a story of spectacular failures. Twice, researchers declared victory. Twice, they were wrong. The field nearly died both times.

What finally worked? That question matters more than any timeline.

The Promise Nobody Could Keep

Before diving into chronology, understand what makes AI history unusual among technology stories. Early researchers weren’t incrementally improving an existing tool like the telephone or the automobile. They were claiming that thinking, the thing that makes humans human, could be manufactured. They were claiming it would happen soon.

In 1970, Life magazine published an article quoting Marvin Minsky: “In from three to eight years we will have a machine with the general intelligence of an average human being.” Minsky later disputed ever saying this. But the quote circulated. It set expectations. And when eight years passed with nothing close to human-level intelligence, people noticed.

This pattern repeated for decades. Bold claims. Funding. Disappointment. Backlash. Repeat.

Why does this matter now? Because you’re hearing similar claims today. Understanding what went wrong before helps you evaluate what might go wrong again.

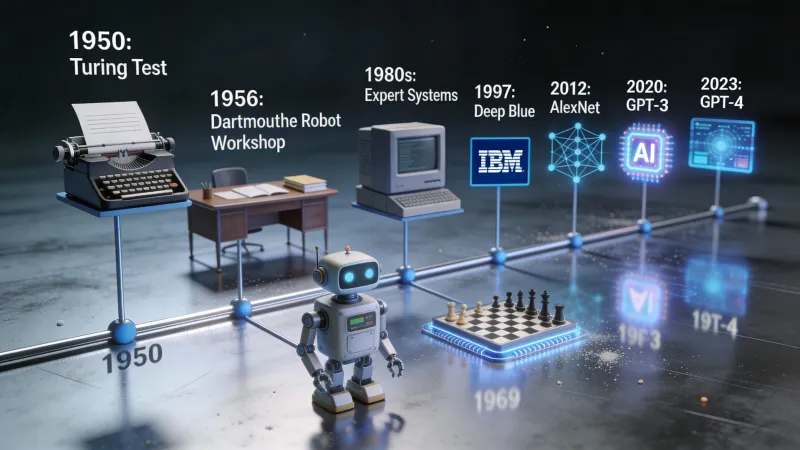

1950: One Question Changes Everything

Alan Turing published a paper in 1950 that framed the entire field before the field existed. The paper was called “Computing Machinery and Intelligence.” The opening line was simple: “I propose to consider the question, ‘Can machines think?’”

Turing knew definitions would be a problem. What does “think” even mean? So he proposed a workaround. Forget trying to define thinking. Instead, play a game.

A human judge has text conversations with two hidden participants. One is human. One is a machine. If the judge cannot reliably tell which is which, does it matter whether the machine “really” thinks?

This became the Turing test. It shifted the debate from philosophy to engineering. Can we build something that passes? That question could actually be answered through experiments, through building and testing and iterating.

Turing died in 1954. He never saw AI research become a field. But his framing still influences how we evaluate AI systems today.

1956: Summer Camp for the Future

Six years after Turing’s paper, a group of researchers gathered at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire for a summer workshop. John McCarthy organized it. Marvin Minsky was there. So was Claude Shannon, who had invented information theory.

The proposal they wrote contains the sentence that defined everything that followed: “The study is to proceed on the basis of the conjecture that every aspect of learning or any other feature of intelligence can in principle be so precisely described that a machine can be made to simulate it.”

Read that again. Every aspect of learning. Every feature of intelligence. Can be precisely described. Can be simulated by a machine.

This was not a modest claim. This was a bet that human intelligence, whatever it is, could be reduced to rules and computations. That nothing about thinking was fundamentally beyond what machines could do.

The term “artificial intelligence” was coined at this workshop. The researchers who attended became the field’s leaders for the next forty years. They were brilliant. They were also wildly optimistic about timelines.

The 1960s: Optimism Runs Wild

The decade after Dartmouth was productive and exciting and ultimately set up the first crash. Researchers built programs that could prove mathematical theorems, play checkers, solve word problems, and hold simple conversations.

ELIZA appeared in 1966. Joseph Weizenbaum at MIT created a chatbot that pretended to be a psychotherapist. It worked by pattern matching. User says “I am sad.” ELIZA responds: “Why do you say you are sad?” No understanding. Just text manipulation.

Something unexpected happened. Users formed emotional connections with ELIZA. They confided in it. Some believed they were talking to something that cared about them. Weizenbaum was disturbed by this. He spent the rest of his career warning about the dangers of attributing human qualities to machines.

By the late 1960s, researchers were making predictions that seem absurd now. Herbert Simon said machines would do any work a human could do within twenty years. Minsky claimed the problem of artificial intelligence would be “substantially solved” within a generation.

The funding kept coming. DARPA poured money into AI labs. The future seemed guaranteed.

1973-1980: The Ice Age Arrives

Then reality hit.

In 1973, the UK government commissioned mathematician James Lighthill to evaluate AI research. His report was devastating. The key finding: “In no part of the field have the discoveries made so far produced the major impact that was then promised.”

Lighthill argued that AI research had hit fundamental barriers. The “combinatorial explosion” problem meant that real-world tasks had too many possibilities to search through. The clever tricks that worked on toy problems failed on anything resembling actual applications.

Britain slashed AI funding. Research labs that had flourished saw their budgets vanish almost overnight. DARPA, watching from across the Atlantic, got nervous. They began demanding practical military applications instead of pure research. Money dried up in America too.

This was the first AI winter. Not a slowdown. A collapse.

Why did it happen? The promises were too big. The problems were too hard. Computers were too slow. Researchers had mistaken early successes on constrained problems for evidence that general intelligence was close.

The winter lasted roughly seven years. AI became a career risk. Using the term in grant applications could sink your proposal. Researchers who stayed in the field did so quietly, working on narrower problems with less glamorous names.

1980-1987: False Spring

AI came back. The driver was “expert systems.” These were programs that encoded human knowledge as rules. If the patient has fever and cough and exposure to someone with flu, then the patient probably has flu. If the equipment makes grinding noise and the oil level is low, then the bearing is probably failing.

Companies loved this. Businesses could capture what their best employees knew and scale it across the organization. Specialized computers were built just to run expert systems. A company called Symbolics sold AI hardware for hundreds of thousands of dollars per machine.

Investment flooded back in. Corporate AI labs opened. The term “artificial intelligence” was respectable again. By the mid-1980s, the AI industry was worth billions of dollars.

But expert systems had a fundamental problem. They could not learn. Every piece of knowledge had to be programmed by hand. Maintaining them was a nightmare. As the rules accumulated, they became brittle and unpredictable. And when cheaper general-purpose computers from Sun and Apple caught up in performance, the specialized hardware market collapsed.

1987-1993: The Second Winter

The crash was worse the second time. Corporate AI labs closed. Symbolics went bankrupt. The remaining AI researchers rebranded what they did as “machine learning” or “neural networks” or anything that avoided the toxic words “artificial intelligence.”

If you were working on AI in 1990, you probably would not have admitted it at parties.

Yet something important was happening beneath the surface. A small community of researchers kept working on neural networks, a technology that had been dismissed in the 1960s. They improved the algorithms. They waited for computers to catch up. And most importantly, the internet was beginning to generate massive amounts of digital text and images.

The ingredients for the next breakthrough were assembling themselves.

Why the Winters Ended

Here is the part most AI histories skip: why did the winters end? What changed?

Three things changed.

First, computing power kept doubling. Moore’s Law meant that a computer in 2010 was millions of times more powerful than one in 1970. Problems that were computationally impossible became tractable.

Second, data became abundant. The internet changed everything. Suddenly researchers had access to billions of documents, millions of images, recordings of thousands of hours of speech. Neural networks need data the way plants need sunlight. The internet provided enough sunlight to grow something big.

Third, algorithms improved. Backpropagation made training deep neural networks practical. Dropout prevented overfitting. Better architectures like convolutional neural networks worked well for images. Incremental progress accumulated into qualitative change.

None of these factors alone was enough. Together, they created conditions for a breakthrough that would dwarf anything that came before.

2012: The Year Everything Changed

In October 2012, a team from the University of Toronto entered the ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge. The competition required identifying objects in photographs. A million images. A thousand categories.

The team used a deep neural network called AlexNet. Geoffrey Hinton supervised. Alex Krizhevsky did the implementation. Ilya Sutskever contributed key ideas.

They won. That was expected. But the margin of victory shocked everyone.

AlexNet achieved a top-5 error rate of 15.3%. The next best entry had 26.2%. That is not a small improvement. That is a different category of performance. That is the difference between a technology that sort of works and one that actually works.

Hinton later joked about the collaboration: “Ilya thought we should do it, Alex made it work, and I got the Nobel Prize.” The Nobel came in 2024, but the AlexNet result was what made everything else possible.

Within months, every major tech company was hiring neural network researchers. Google acquired a startup Hinton had founded. Facebook opened an AI lab. Microsoft expanded its research division. The money that had abandoned AI in the 1980s came flooding back.

This was not a false spring. The technology actually worked. It worked on real problems at real scale with real economic value.

2017: Eight Researchers Change the World

The next inflection point came from a paper with a strange title. Eight Google researchers published “Attention Is All You Need” in June 2017. The title referenced a Beatles song. The content revolutionized natural language processing.

The paper introduced the transformer architecture. Previous language models processed text sequentially, one word at a time. Transformers process everything in parallel, allowing each word to “attend” to every other word regardless of distance. This made training much faster and captured long-range dependencies in text much better.

Every major language model today uses transformers. GPT. Claude. Gemini. Llama. All of them descended from that 2017 paper. It is probably the most influential AI research of the last decade.

The authors did not know what they had created. The paper was about machine translation. It took years for the implications to become clear.

2020: The Scaling Hypothesis Proves Itself

OpenAI released GPT-3 in June 2020. It had 175 billion parameters. It could write essays. It could debug code. It could answer questions about almost anything. Sometimes it made things up. But when it worked, it worked in ways that seemed almost magical.

The reaction from developers and researchers was intense. One viral tweet captured the moment: “Playing with GPT-3 feels like seeing the future.”

OpenAI’s CEO Sam Altman tried to temper expectations. “The GPT-3 hype is way too much,” he wrote. But the genie was out of the bottle.

GPT-3 proved something important. The scaling hypothesis suggested that if you made neural networks bigger and trained them on more data, they would keep getting smarter. Many researchers were skeptical. GPT-3 showed the skeptics were wrong.

November 30, 2022: The Public Discovers AI

ChatGPT launched on a Wednesday. Five days later, OpenAI CEO Sam Altman tweeted: “ChatGPT launched on wednesday. today it crossed 1 million users!”

Two months after that, it had 100 million users. No consumer application had ever grown that fast. Not Facebook. Not TikTok. Not Instagram. Nothing.

What made ChatGPT different from GPT-3? It was free. It was conversational. It was optimized to be helpful and harmless. Anyone could try it without an API key or a credit card.

This was the moment AI stopped being a technology story. Your coworkers were using it. Your parents were asking about it. Your kids were doing their homework with it.

The field that had nearly died twice was now the most talked-about technology in the world.

Where Are We Now?

As of early 2026, ChatGPT has 800 million weekly active users. That is roughly 10% of the world’s adult population using one AI tool. GPT-5 exists. Claude exists. Gemini exists. Open-source models from Meta and Mistral have made powerful AI accessible to anyone with decent hardware.

The money flowing into AI dwarfs anything from previous booms. Hundreds of billions of dollars. New data centers being built on multiple continents specifically to train AI models.

Is this another bubble? Will there be a third winter?

The honest answer: nobody knows. But some things are different this time.

The technology delivers real value. ChatGPT is not ELIZA. It can actually help with actual work. Companies are using AI to write code, analyze data, summarize documents, and dozens of other tasks that save real time and money.

The capabilities are demonstrable. Previous AI booms ran on promises. This one runs on products people can use today.

The risks are real. These models sometimes hallucinate. They can be manipulated. They raise questions about jobs, misinformation, and concentration of power that earlier AI systems never posed.

The Pattern Worth Remembering

Seventy-five years of AI history teach a consistent lesson. Breakthrough leads to hype. Hype leads to overpromising. Overpromising leads to disappointment. Disappointment leads to winter.

The breakthroughs since 2012 are real. Transformers changed what is possible. ChatGPT changed who uses it. But history suggests humility about predictions.

The researchers who said human-level AI was twenty years away in 1965 were wrong. The researchers saying similar things today might be wrong too. Or they might be right. The honest answer is that nobody knows.

What we do know: AI tools are useful now for specific tasks. Understanding where they came from helps separate reality from hype. That separation has value.

The field that died twice is now worth trillions. Whether it stays that way depends on whether the technology keeps delivering. So far it has. But we have been here before.